(This article is part of the BGC Rewrite Series)

In QBASIC, drawing graphics was easy. You set a “graphics” screen mode and started drawing. QBASIC offered several primitives:

- PSET (draw a single pixel)

- LINE

- CIRCLE

and of course, for more complex shapes, there was the DRAW command:

…which is the subject of of another article.

In this article, I discuss the process I used for choosing a graphics library.

Preliminary requirements

For me, the important features were:

- Simple to use

- Minimal dependencies

- .NET compatable

- Capable of primitive graphics (pixels, lines, circles etc)

The following sections detail my experience with XNA/MonoGame, OpenGL via OpenTK and SDL1/SDL2.

If you want to skip all that, I ended up going with SDL2.

XNA/MonoGame

I actually started a BGC rewrite (which was actually a rewrite of a PureBASIC rewrite of BGC QBASIC version) in C# + XNA framework. Naturally, I was also learning Object Oriented Programming at the time, and the game quickly stalled due to getting stuck on architecture.

I revisited XNA in the form of MonoGame… But quickly dropped it when I realised I could not do primitives such as pixels and lines (easily). If you were doing sprite based graphics, this library would be superb.

OpenGL via OpenTK

The next library I looked at was OpenGL via OpenTK. This seemed like an obvious choice, as it met all 4 of my important features above.

And OpenTK existed as a fantastic interface to .NET meaning F# interop would be easy. It took me all of 15 minutes to get a demo up and running in FSI.

The example code was adapted from Laurent Le Brun’s tutorial on OpenTK and F#, and here is that example adapted for FSI:

//example adapted from http://laurent.le-brun.eu/site/index.php/2010/06/23/57-fsharp-opengl-a-cross-platform-sample

#r @"c:\dev\OpenTK.dll"

open System

open System.Collections.Generic

open OpenTK

open OpenTK.Graphics

open OpenTK.Graphics.OpenGL

open OpenTK.Input

type Game() =

/// <summary>Creates a 800x600 window with the specified title.</summary>

inherit GameWindow(800, 600, GraphicsMode.Default, "F# OpenTK Sample")

do base.VSync <- VSyncMode.On

override o.OnLoad e =

base.OnLoad(e)

GL.ClearColor(0.1f, 0.2f, 0.5f, 0.0f)

GL.Enable(EnableCap.DepthTest)

override o.OnResize e =

base.OnResize e

GL.Viewport(base.ClientRectangle.X, base.ClientRectangle.Y, base.ClientRectangle.Width, base.ClientRectangle.Height)

let mutable projection = Matrix4.CreatePerspectiveFieldOfView(float32 (Math.PI / 4.), float32 base.Width / float32 base.Height, 1.f, 64.f)

GL.MatrixMode(MatrixMode.Projection)

GL.LoadMatrix(&projection)

override o.OnUpdateFrame e =

base.OnUpdateFrame e

if base.Keyboard.[Key.Escape] then base.Close()

override o.OnRenderFrame(e) =

base.OnRenderFrame e

GL.Clear(ClearBufferMask.ColorBufferBit ||| ClearBufferMask.DepthBufferBit)

let mutable modelview = Matrix4.LookAt(Vector3.Zero, Vector3.UnitZ, Vector3.UnitY)

GL.MatrixMode(MatrixMode.Modelview)

GL.LoadMatrix(&modelview)

GL.Begin(BeginMode.Triangles)

GL.Color3(1.f, 1.f, 0.f); GL.Vertex3(-1.f, -1.f, 4.f)

GL.Color3(1.f, 0.f, 0.f); GL.Vertex3(1.f, -1.f, 4.f)

GL.Color3(0.2f, 0.9f, 1.f); GL.Vertex3(0.f, 1.f, 4.f)

GL.End()

base.SwapBuffers()

let run () =

let game = new Game()

do game.Run(30.)

This example assumes you have OpenTK.dll at c:\dev. To run the example, copy and paste the code into FSI and call run();;

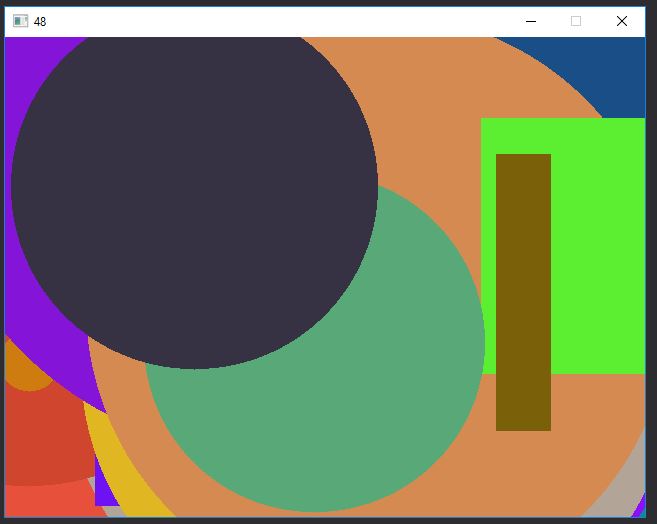

Here is that example running:

It could not be simpler, right? So, what made me drop OpenGL? Well… Apparently learning OpenGL 1.1 is “not ok”.

Above: from Stackoverflow

OpenGL moved away from the simpler but more limited “Fixed Function Pipeline”, and towards more power and control over the graphics pipeline via “Shaders”. No doubt in response to feedback from the Gaming community where performance is critical. And this is perfectly fine.

But to say that it’s wrong to learn OpenGL 1.1 if all you need is simple graphics (i.e. scientific visualisation or simple vector graphics rip offs of more popular games) is also wrong. There is a saying: “use the right tool for the job.”

Anyway, I found this particular discussion quite hilarious, and I think it demonstrates why OpenGL 1.1 is still around

Above: from Why so much obsolete GL

And then there is GLSL aka “OpenGL Shader Language”, which appears to be yet another C like language for controlling shaders. The thought alone of learning GLSL annoys me.

At the end of it, I realised I was not writing a game engine and took this bit of advice:

“If you want to learn OpenGL, learn 3.2+ Core. If you want to make games, use Unity. There is literally no place for OpenGL 1.x or 2.x that wouldn’t be better served by using a library.”

From that perspective I guess I don’t want to learn OpenGL, I just want to do simple graphics. In which case, a library (such as SDL, say) would be more appropriate.

The final nail in the coffin was that doing pixel graphics would be somewhat difficult too. So I looked to SDL.

SDL and SDL2

I remember looking at SDL a long time ago when I was still trying to use OS/2 as my primary operating system (yes). At the time, any game I created needed to be able to run on OS/2 as well as Windows (note: this is no longer a requirement). If my memory serves me correctly, I was quickly turned off for two reasons:

- SDL only provided the bare minimum in terms of rendering. You had the ability to blit sprites to the screen; everything else – such as sprite rotation – had to be provided via a library.

- There was no hardware acceleration

Despite this, I decided to look at SDL again and see if the situation had changed.

Like OpenGL, getting an SDL example running was very simple. The example code here was adapted from David Bolton’s tutorial on SdlDotNet. The code uses the SdlDotNet library, a .NET wrapper around the SDL library (more specifically SDL_gfx), with their own helpful classes. Although the fact that the Screen object draws rectangles, yet the Circle class draws itself on a screen is a bit annoying with the inconsistent API.

Below is the F# version of David Bolton’s example, which assumes you have SDL.NET installed in Program Files (x86):

//example adapted from https://www.thoughtco.com/programming-games-using-sdl-net-958608

#r @"C:\Program Files (x86)\SdlDotNet\bin\SdlDotNet.dll"

#r @"C:\Program Files (x86)\SdlDotNet\bin\Tao.Sdl.dll"

open System

open System.Drawing

open SdlDotNet.Graphics

open SdlDotNet.Core

open SdlDotNet.Graphics.Primitives

let wwidth = 1024

let wheight = 768

let r = new Random()

let QuitEventHandler(args) =

Events.QuitApplication() ;

let TickEventHandler (screen:Surface) (args:TickEventArgs) =

for i = 1 to 17 do

let rect = Rectangle(Point(r.Next(wwidth- 100),r.Next(wheight-100)),

new Size(10 + r.Next(wwidth - 90), 10 + r.Next(wheight - 90)))

let Col = Color.FromArgb(r.Next(255),r.Next (255),r.Next(255))

let CircCol = Color.FromArgb(r.Next(255), r.Next (255), r.Next(255))

let radius = int16 (10 + r.Next(wheight - 90))

let Circ = Circle(Point(r.Next(wwidth- 100),r.Next(wheight-100)),radius)

screen.Fill(rect,Col) |> ignore

Circ.Draw(screen, CircCol, false, true)

screen.Update()

Video.WindowCaption <- Events.Fps.ToString()

let run () =

let screen = Video.SetVideoMode(wwidth, wheight, 32, false, false, false, true)

Events.TargetFps <- 200;

Events.Quit.Add(QuitEventHandler)

Events.Tick.Add(TickEventHandler screen)

Events.Run()

Again, you can paste directly into FSI and type run();;

Actually, I noticed while writing this article that the example code from ThoughtCo contains a performance issue. Every time a circle and rectangle are drawn on the screen, a call is made to update the screen, instead of rendering all shapes and calling update.

Below is the code as shown on the tutorial page:

private static void TickEventHandler(object sender, TickEventArgs args)

{

for (var i = 0; i < 17; i++)

{

var rect = new Rectangle(new Point(r.Next(wwidth- 100),r.Next(wheight-100)),

new Size(10 + r.Next(wwidth - 90), 10 + r.Next(wheight - 90))) ;

var Col = Color.FromArgb(r.Next(255),r.Next (255),r.Next(255)) ;

var CircCol = Color.FromArgb(r.Next(255), r.Next (255), r.Next(255)) ;

short radius = (short)(10 + r.Next(wheight - 90)) ;

var Circ = new Circle(new Point(r.Next(wwidth- 100),r.Next(wheight-100)),radius) ;

Screen.Fill(rect,Col) ;

Circ.Draw(Screen, CircCol, false, true) ;

Screen.Update() ;

Video.WindowCaption = Events.Fps.ToString() ;

}

}

Based on the indentation, it looks like the author intended to update the screen and FPS after the for loop, but has accidently placed the curley brace after the screen update. Making that adjustment improved the performance considerably, although my laptop still tops out at about 75 frames per second, or 2550 primitives per second.

For unaccelerated performance, that is blazing fast. Well, if you’re happy to run at 1024x768, at least. At higher resolutions it starts to slow down to the 40 mark.

In SDL 1, there is no hardware acceleration. Undeterred, I did some research to see how hardware acceleration might be obtained. It turns out that there is SDL 2, which provided some improvements over SDL 1; chief among those being hardware acceleration, and primitive drawing operations (so no real need to rely on third party libraries). Exactly what the doctor prescribed!

At present however, the .NET bindings available consist of nothing more than the standard interop interface. I decided to give it a crack anyway. One thing I discovered is that interop in F# is a bit more awkward than in C# due to F# not allowing implicit conversions.

I also had to download and compile the SDL2 C# wrapper project at https://github.com/flibitijibibo/SDL2-CS. I named the compiled DLL SDL2CS in order to distinguish it from SDL.DLL

Adapting the code from the SdlDotNet example was not complete – it did not render circles so I just doubled the number of rectangles – but otherwise I was getting 4148 primitives per second at 1024x768.

Again, this example assumes you have a compiled SDL2CS.dll at c:\dev

#r @"C:\dev\SDL2CS.dll"

#nowarn "9"

open System

open System.Drawing

open Microsoft.FSharp.NativeInterop

open System.Runtime.InteropServices

open SDL2;

let wwidth = 1024

let wheight = 768

let r = new Random()

let getRandomRgb () = byte (r.Next(255)), byte(r.Next(255)), byte(r.Next(255))

let getRgb format = SDL.SDL_MapRGB(format, byte (r.Next(255)), byte(r.Next(255)), byte(r.Next(255))) //Color.FromArgb(r.Next(255),r.Next (255),r.Next(255))

let getPoints(min, max) = (min + r.Next(wwidth- max),r.Next(wheight-max))

let getPoint() = getPoints(0, 100) |> Point

let getRect(point:Point, size:Size) =

SDL.SDL_Rect(x = point.X, y = point.Y, w = size.Width, h = size.Height )

let setDrawColor (r:byte, g:byte, b:byte) renderer = SDL.SDL_SetRenderDrawColor(renderer, r, g, b, 0uy)

let getCirc() = ()

let run () =

SDL.SDL_Init(SDL.SDL_INIT_VIDEO)

let window = SDL.SDL_CreateWindow("SDL2", 100, 100, wwidth, wheight, SDL.SDL_WindowFlags.SDL_WINDOW_SHOWN)

let renderer = SDL.SDL_CreateRenderer(window, -1, SDL.SDL_RendererFlags.SDL_RENDERER_ACCELERATED)

let mutable counter = 0

use timer = new System.Threading.Timer((fun callback -> printfn "FPS %d\r\n" counter; counter <- 0), null, 1000, 1000)

while true do

SDL.SDL_PumpEvents() //this is needed otherwise the UI eventually locks up

for i = 1 to 34 do

let mutable rect = getRect(getPoint(), getPoints(10, 90) |> Size)

renderer |> setDrawColor (getRandomRgb())

SDL.SDL_RenderFillRect(renderer, &rect) |> ignore

renderer |> SDL.SDL_RenderPresent

counter <- counter + 1

()

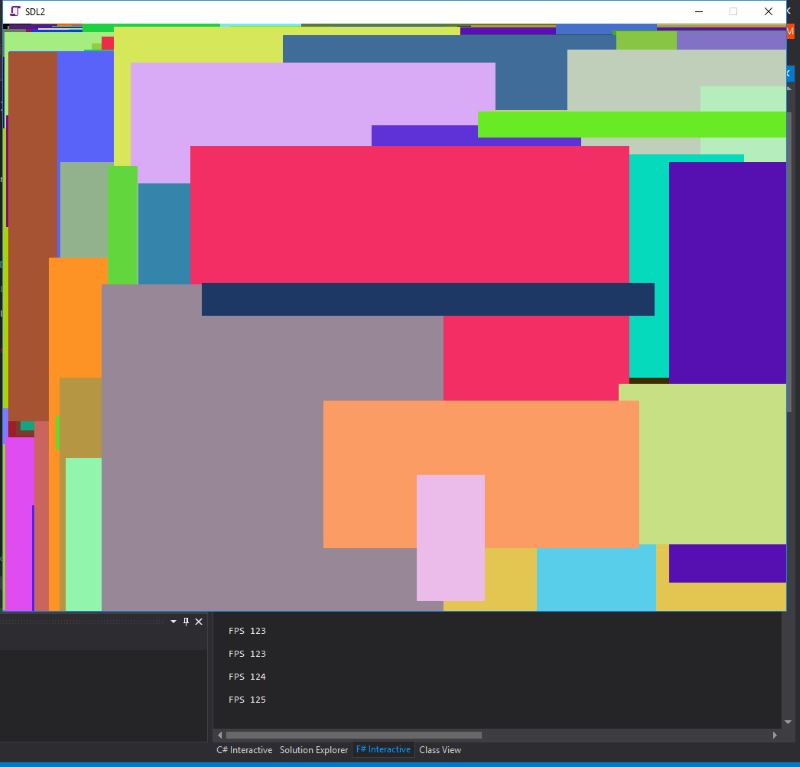

And here is the output from that program:

This is almost double the performance of SDL 1, however I soon discovered – while writing this article in fact – that this was an unfair comparison.

A note about comparing performance

When making performance comparisons, it pays to ensure both environments are as equal as possible in their setup.

In this particular case, drawing a circle is a much more costly operation than drawing a rectangle. Simply doubling the number of rectangles is not the same as drawing 17 circles and 17 rectangles.

When I fixed the SDL1 code to also draw 34 rectangles like the SDL2 example, I actually hit a conundrum: the SDL1 example was rendering at the same framerate – sometimes about 10FPS faster! How could this be, if SDL1 was unaccelerated?

I investigated the problem on the assumption that the SDL2 setup was somehow not running in accelerated mode, so I set out to prove that.

The following code is able to query what drivers are available:

let drivers = List.init (SDL.SDL_GetNumRenderDrivers()) (fun i ->

let info = SDL.SDL_GetRenderDriverInfo(i) |> snd

info.name |> Marshal.PtrToStringAnsi

)

And this is the output:

val drivers : string list = ["direct3d"; "opengl"; "opengles2"; "software"]

Next, after creating the renderer with SDL_RendererFlags.SDL_RENDERER_ACCELERATED, I used this bit of code to query what it picked:

let info = SDL.SDL_GetRendererInfo(renderer) |> snd

info.name |> Marshal.PtrToStringAnsi

and the output was:

val it : string = "direct3d"

Now I was scratching my head. I could not find any particular cases where software rendering would be as fast or faster than hardware – except if the drivers were bad.

Recall that I am developing this on my 2008 era laptop: a HP Compaq 6710b with Intel Centrino based Core 2 Duo T8300 @ 2.4GHz, and no graphics card to speak of an Intel Mobile 965 graphics card. I was starting to suspect that the provided drivers did not provide any real advantage over the software renderer.

This suspicion was further confirmed when I tried the SDL2 example using SDL_RendererFlags.SDL_RENDERER_SOFTWARE. SDL_GetRendererInfo confirmed that the driver was “software”, yet the speed did not really decrease from 120 FPS. It was clear that I needed to test this on a real gaming machine. And by real I mean a machine that has an actual graphics card ;)

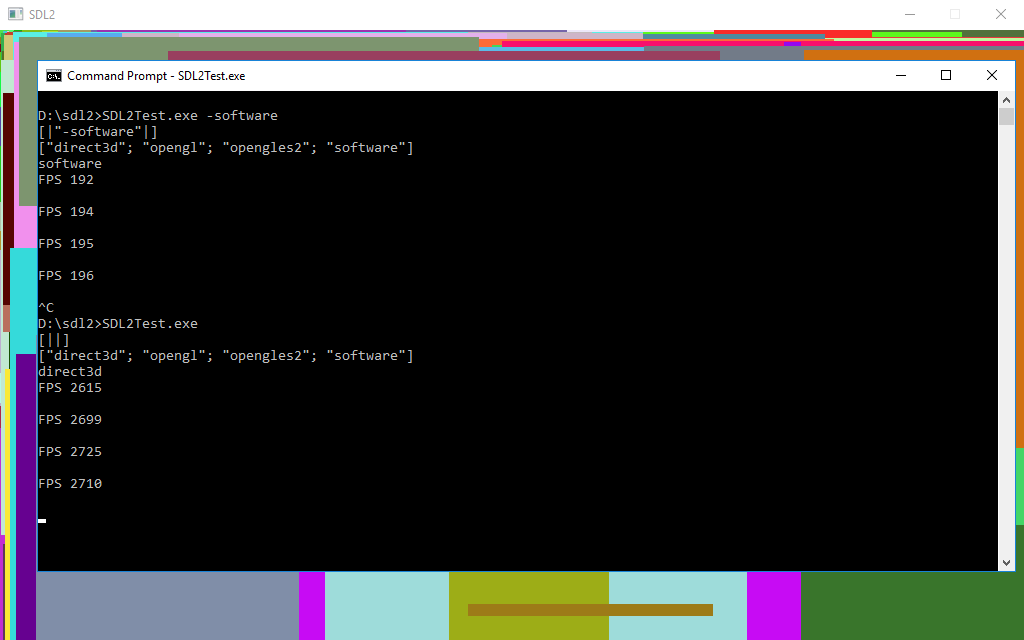

I created a console app that could switch which renderer to use based on a command line argument. The difference between software and hardware rendering was night and day:

An almost 14x increase in speed over the software renderer. And 190FPS is not slow, either. A similar test program using SDL1 maxed out at 190FPS too.

The “real” gaming PC in question is my 2010 era Intel i5 760 with ATI 5770. Not exactly modern any more, but it did the trick.

Conclusion?

It’s worth mentioning that over 2500 filled primitives per second was technically already quick enough for my purposes, considering that I only need to do vector graphics. What led me to investigate SDL2 was the flawed example producing only 500 filled primitives per second. What I simply wanted to check is if hardware acceleration was actually working.

If you find you are getting bad performance, you might simply end up proving your PC has a poor performing graphics card :P

SDL1 or SDL2?

If you’re wondering if you should go with SDL1 or SDL2, I can only offer food for thought:

- SDL1 has been around longer than SDL2.

- SDL1 is fast enough. Honestly.

- SDL1 has lots of language bindings and third party libraries.

However

- SDL1 is not being maintained anymore.

- SDL1 is not hardware accelerated like SDL2. And SDL2 has heaps of other improvements over SDL1.

I am going with SDL2 as it meets my four criteria

- Simple to use

- Minimal dependencies

- .NET compatable

- Capable of primitive graphics (pixels, lines, circles etc)

SDL.NET still requires more DLLs compared to using pure SDL2. And as stated earlier, it’s interface was a tad annoying.

End of Article

Damn. Once again, another massive article. I do try to keep these things short, but honestly I probably should be a politician.